Wherein I undertake a zealous search for clues about my ancestress from two early photographs…

If you had been told story after fantastic, toe-curling story about your family lineage for years, using only your imagination to fill in the details of what your direct ancestor might have looked like… What would you do when you finally stumbled across an actual photograph, however grainy, however obscure?

The woman pictured above is Suzanne Marguerite Dufour Golay, my great-great-great-great-great grandmother. I took this photo with my iPhone, hovering the lens carefully over the printed image I’d found in a book. From the half-tone patterning, I deduced that the printed image is likely a scan or xerox/facsimile taken of the original photograph. How many times it was copied, I may never know. This JPEG I’ve posted could be three or four times removed from the original at this point.

How many hours have been spent staring at this image? A picture is worth at least a thousand words, but this blog post will go far beyond that. I have less than a hundred dots per inch to work with (that’s designer-speak for 100 DPI; low resolution), which is some super sparse detail. What color was her hair? Her eyes? How old was she? I want to see the details of her dress, what kind of lace surrounds her face. But the closer you zoom in, the more the image separates. It’s maddening.

At first glance, this could be a tintype, daguerrotype, or ambrotype. Its size, material, and casing would provide helpful clues, but I only have this copy of a copy (of a copy?). But we do know this: daguerreotypes were in use in the United States from roughly 1840-1855, at which point ambrotypes came onto the scene, which were cheaper to make. Tintypes were also in use, and all the rage during the Civil War. Loads of these have survived; they’re hardier than daguerreotypes. But all of these direct image format technologies overlapped one another, and the date ranges are imprecise. This site breaks down the differences between their appearances and compositions.

Suzanne Marguerite Dufour Golay was born in 1785 in Montreux, Switzerland. She was living in the town of Vevay in Indiana Territory by 1806. I am told that Cincinnati, the nearest urban center, had a daguerreotype studio by 1840, when Suzanne would have been 55 years old. The people of Vevay could travel easily up the Ohio River to Cincinnati by steamboat in the mid nineteenth-century, but Vevay would likely have added its own studio by 1850, if not sooner, when Suzanne was 65. Suzanne died in 1865 at the age of 80.

The book that contains this photo, David Golay, His Ancestors and Descendants, is no longer in print. When my grandmother, Eunice Elizabeth Golay Ferguson, first shared it with me years ago, she was proud to point out that I was the final entry–the very last descendant to be added to the family tree in 1983. My grandmother said she called the author as soon as she got the news that I had been born, to see if there was still time to include one more name before the book went to the printer.

The Golay Tome, as I call it, has become an invaluable resource for me, as it contains all of the genealogy research compiled by Ruby Levonne Golay (Stoner). I borrowed it a few years ago from my aunt and am still jealously guarding this priceless work until I am asked to return it. In the meantime, I am in the process of researching a digitization of the work, so that it can be shared more widely with other descendants and researchers. But I digress.

When I could not reach the author (Ruby sadly died in 2022), I tried to discover who, among the descendants, might have contributed this photo of Suzanne. For all of Ruby’s thorough documentation, I discovered a few discrepancies and inconsistencies in her work. My best guess was that the photo had come from the scrapbook of Marjorie Golay McNamara (great-granddaughter of Suzanne), who died in 1991. Through some sleuthing on the internet, I tracked down Marjorie’s granddaughter, and… Cold-called her.

How does one explain, quickly and succinctly, their reasons for calling a perfect stranger, their hopes for further information, based on the purest of intentions, and also, by the way, that they happen to be a distant relation… Before the person on the other end of the line hangs up?

Thankfully, Heather was patient… And intrigued. She regretfully informed me, however, that IF such a scrapbook, or box of mementos containing a certain daguerreotype, still existed, it would be in the attic of her ailing stepmother’s home in a small town in Ohio, and it would be quite impossible to explore that collection any time soon. A dead-end.

As that door closed, I resolved to let go of my search. But then, in early 2023, another Dufour descendant, Christy Williams, entered my life. Through my persistent digging (and cold-calling), I have been fortunate to connect with other Dufour descendants over the past several years. Ellen Stepleton, author of Envisioning New Switzerland: A Founding Document for the Swiss Colonists at Vevay, Indiana is one such treasure, and a wealth of knowledge across a wide range of subjects. According to Ellen, Christy Williams had inherited a box of Julia LeClerc Knox’s documents, which included a few (gasp) photographs.

Christy emailed me several images from her collection, most of them unlabeled. Did any of them look familiar to me, she wondered? She had already correctly identified Elisha Golay (Suzanne’s husband), and I was able to identify their eldest son Constant (Suzanne’s son) and his wife, Louisa Morerod Golay.

There are moments wherein time seems to slow, and even stop. When I saw this woman, I remember my quick intake of breath. I scrambled to find the snapshot of Suzanne, to compare them, side-by-side. This image was remarkably CLEAR. I could see the finer details of this woman’s clothing, her gloves, the objects in her hands, the floral motif on the tablecloth at her side. Wow, wow, wow.

She is alone; the background of the image is a dark void. Her arm rests on a small table, supporting her. In her right hand, she holds what appears to be a small box or book with a metal clasp, slightly out of focus. Her left hand grasps what looks like a stylized metal feather, perhaps a brooch, hair ornament, or other decorative item. Is it related to the other object? So. Many. Questions.

“Do you have the original?” I asked. What luck; she did… And I was able to see it for myself, later that spring, when Christy happened to be in town.

I took this ridiculous photo to show the reflective, mirror-like surface of the print, which I handled with the utmost care, touching only the edges. There was no marking on the back; a studio would have put that on the hinged case, which was missing. I could only see the positives or negatives (shadows or highlights) of the image, based on how the image was angled and tilted towards the light. Extraordinary! Based on its size, mercurial silver appearance, and tarnishing at the edges, I believe it to be a sixth-plate daguerrotype. Since the plate had lost its frame and protective case, I advised Christy to keep it safely tucked away from light. I admit I wanted to keep it. I wanted to take it immediately to a preservationist and have it cleaned and enclosed properly for conservation.

In the Golay Tome, I found a letter from Christy’s ancestress, Louisa Morerod Golay, Suzanne’s niece and daughter-in-law (it’s okay to cringe, I certainly still do) to a cousin in Geneva, Adolphe Piguet, in 1877. In her post-script, Louisa wrote:

P.S. My husband is sending you the portraits of his parents. His father’s is very good. The one of his mother, not so good.

…Not so good. The photo of his mother would have been Suzanne. Photographs from the time were fragile and certainly deteriorated easily, and I would not be surprised if the above black-and-white scan of Suzanne is all that remains now of the original. I won’t bore you, dear reader, with the details of how I tried to track down a certain Humbert Golay, who had Louisa’s letter in his private collection of family artifacts, to discover if perhaps his descendants had kept whatever photographs Louisa sent to Switzerland in 1877. It was the longest of long shots, and long story short: I reached another dead end.

So, what do you think? Is the second image also Suzanne? Are these women one and the same, taken a few years apart? The black-and-white image shows an older woman, but I believe the resemblance is uncanny: the wide-set eyes, downturned mouth, soft eyebrows, gentle jowls… It was a common hairstyle they’re wearing, split down the middle, so I won’t cite that as hard evidence. However, the daguerreotype’s subject has smooth features, possibly enhanced by a slight overexposure. Suzanne’s black-and-white portrait shows a much more weathered face, lined with age… Or is that just the damage and deterioration of the print that we’re seeing? Both women have dark hair, but that is actually a Golay trademark; my grandmother Eunice is 90 years old and she does not have uniformly gray or white hair. It remains an amiable mousey brown.

My initial theory was that the woman in the black collar and lace gloves might be Suzanne’s only daughter, Clarissa (Clarisse). But here’s a curious fact: according to the Golay Tome, Clarisse Golay Armington died around 1850, at the age of 38, in Greensburg, Indiana. However, this headstone in the South Park Cemetery at Greensburg suggests that Clarisse died in 1844, at age 31. So, how old do we think these women are? Can we estimate when these were portraits taken?

Having one’s portrait taken in the mid-nineteenth century was not yet routine, and costly enough that pains were taken to highlight details and communicate certain distinctions for posterity. People often wore their best clothing, or borrowed someone else’s. They displayed their prized possessions. We’re no different today with our social media filters, still seeking to polish the way we are seen and perceived. We want to highlight and commemorate noteworthy occasions, special moments, and milestones.

I studied the daguerreotype at length, for clues. In Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900 by Joan Severa, I learned that there were layers of meaning hiding in these unassuming portraits. The attire and accessories of the sitter were often carefully planned, with nearly every item holding some sort of significance. The use of props and backdrops was almost always intentional, as with painted portraits.

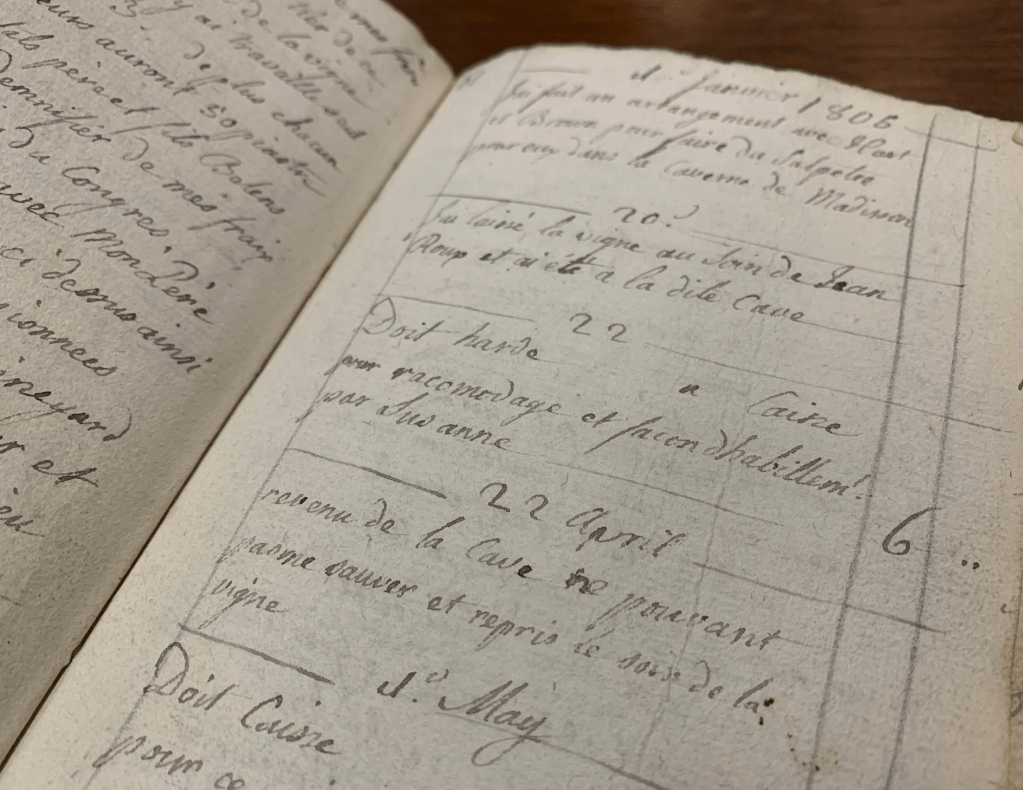

When I was able to review Jean Jacques Dufour’s daybook/diary in the Indiana State Library archives in 2021, I saw that he noted on the 22nd of January, 1805/6 that he had paid his younger sister, Suzanne Dufour, to make and mend clothes for him:

‘Doit hardes a laine pour raccommodage et façon d’habillement par Susanne’ roughly translates to ‘owe [for] woolen clothes, mending and dressing by Suzanne’. I have corrected a few spelling and grammatical errors for clarity. It looks like he paid six bucks, which would be around $150-160 in today’s money. The fact that JJ paid his sister for her work is something I’d love to unpack, but I will save this for another discussion. The point is, like many other women of the time, Suzanne was an able seamstress.

Is the rather conservative dress in the photo handmade? Would it be considered economical, everyday wear, with modest trimmings, or is the style fashionable, the fabric expensive? The woman is wearing an elbow-length cape called a pelerine, which matches the dark cloth of her dress, black filet mitts, or fingerless lace gloves, and a white daycap with ruffles. If only I could have Joan Severa review the daguerreotype and give me her expert opinion! Alas, she died in 2015, so I must comb her book for information instead. Here are some notes from Dressed for the Photographer:

“Several construction details are especially associated with women’s dresses in the 1840s… an extremely fine piping was frequently used on all bodice sleeves, even down the sleeve. Bodices were very long and tight and were pointed in front through most of the decade, shortening somewhat in front, lengthening at the sides, and taking on a rounded dip at the front at the end of the decade. A very short waist with a rounded point and fan bosom shows up in the photographs in everyday dress at the very end of the decade and into the fifties, but is mainly seen on elderly women. Speculation is that this style reflected the leaving off of the fashionable long, rigid corset for comfort in middle age.” (Severa 8)

“A daycap of more or less sheer white cotton is associated with 1840s dress, both everyday and dressy attire… early in the decade the cap was worn by both young and old and [later] in the decade it may have been relegated to older women.” (Severa 10)

“Only older women tied [daycap] strings snugly under the chin.” (Severa 83)

“The daycap is so rarely seen in the photograph of the fifties that it must be considered not to have been in fashion, at least for streetwear.” (Severa 101)

“The wearing of mitts, or fingerless gloves, of knitted silk or openwork is another detail left mostly to the understanding of the women of the time. The photographs show very young girls, some well-dressed young women, and many older ladies wearing mitts. From written references to their accustomed use with dinner and party dress, it is clear that mitts were not for everyday wear. Patterns and instructions were included in some periodicals, indicating that they were sometimes made at home, knitted or netted of silks, most popularly in black.” (Severa 11)

Black collars, Severa writes, were often worn by people who were in mourning, as an outward symbol of their grief. Could it be possible that the daguerreotype above shows Suzanne Marguerite Dufour Golay in 1850, aged 65, wearing late 1940s mourning attire to grieve the recent death of her daughter at a daguerreotype studio in Vevay, Indiana? Is she holding cherished items that belonged to or reminded her of Clarisse? Was this image commissioned to capture the depth of her loss, before it began to take its toll on her physical features? It has been shown that women age abruptly and their appearance can shift dramatically at certain points in their lives; one of these chapters is their early sixties.

I have no proof that the woman in the daguerreotype is Suzanne, only a feeling, a hunch; like Philippa Langley, who simply knew that King Richard III was buried underneath that car park in Leicester, England. My theories are supported by the fact that the photograph was originally in the possession of Julia LeClerc Knox, author of the Dufour Saga, collector of artifacts from the founding families of Vevay. The photograph was with other members of Suzanne’s immediate family; it is very likely a Golay or Dufour relative or descendant, and Suzanne was part of both families. The window of time for daguerreotypes, and more specifically, portrait studios in Vevay, Indiana, aligns with Suzanne’s apparent age in the image, emphasized by her clothing styles.

The longer I looked at the photo, I got the fanciful idea that this was Suzanne, holding a quill and journal, imploring her future descendant to keep working on the damn novel. Onward.

Leave a comment